Simple thin metal bands at first glance, but for those who know them well, there’s a fascinating world of context and applications within these unassuming little archwires. Archwires are used in braces to deliver force via tension, as well as impose alignment and control over the movement of a patient’s teeth. What this means, is that archwires are the operative force behind braces, and are what Orthodontists use to slowly re-shape the positions of a patient’s teeth.

There are three primary materials used in contemporary orthodontic archwires, each of which having different qualities which make them better-suited to particular roles in ortho work. These materials are the following:

Stainless Steel - SS: Highest tensile and yield strength. These wires do not rust and can be adjusted in a number of ways without breaking. However, Stainless Steel does not have a high level of elasticity, meaning they are not typically used in early orthodontic work.

Nickel-Titanium - NiTi: More elastic wires, will return to their original shape. Used to apply gentle, steady force at the beginning of orthodontic procedures. Some of these wires can be heat activated, which means they can be worked at room temperature, but will return to their original shape when their temperature reaches the level of the patient’s mouth. This gives them enhanced ease of use without sacrificing elasticity or force.

Beta-Titanium – TMA: This material often considered the halfway point in tensile strength and elasticity between NiTi and SS. Beta-Titanium has more tensile strength than NiTi, and more elasticity than Stainless steel. Additionally, this wire can be deformed and it will not return to its original shape.

Each of these archwire materials has their own place in the dental practice, different applications and use cases. Regardless of their material, archwires are versatile, being able to be applied to put steady pressure on teeth of any alignment, with different benefits from different types of bracket systems. We’ll be talking about these points, and more in detail within this extended blogpost on the wonderful world of archwires.

The History Of Archwires

Archwires have been around for a long time. So long in fact that their origins are quite murky. A commonly-known fact is that the first archwires for orthodontic work were invented in around 1728 by Pierre Fauchard. Except these weren’t orthodontic archwires, this was the "Bandeau”, a thick strip of metal used to slowly force teeth into alignment. Similar in principle to modern archwires, but very different in its execution. But not even Pierre can lay claim to the title of “inventor” of the orthodontic archwire, the AAO (American Association of Orthodontics) announced that mummified corpses have been found with metallic bands wrapped between their teeth, seemingly to correct their alignment in a manner similar to archwires. From roman tombs in Egyptian land, to historical accounts of devices designed to re-align crooked teeth, our history is replete with rudimentary orthodontic work.

However, we'll be narrowing our scope to the last few centuries, back to the age of Pierre and his Bandeau. In the early 19th century, orthodontic work was performed using a variety of metals, from precious gold and platinum to wood. Gold alloys were the standout Orthodontic material of choice because of their corrosion resistance and inherent malleability. As metallurgic developments meant cheaper materials could be used to achieve the same, or greater outcomes, gold was quickly ushered out in the mid-20th century.

Stainless steel’s advent in the 20th century was a significant step. Orthodontic archwire work –while still expensive – was made cheaper. Stainless steel’s unique material properties also allowed for a new form of technique or ‘mechanic’. Prior to the use of stainless steel, loop mechanics were the primary means of delivering controlled forces to assist in the correction of teeth. With the use of stainless steel and its unique properties, sliding mechanics were enabled as a means of orthodontic work.

In the 1970’s developments in adhesives meant that direct bonding became possible, as well as the self-ligating bracket. Self-ligating brackets are an important means of retaining a level of aesthetics for some patients, and they help to minimise the friction which slows down the movement of teeth in sliding mechanics.

Developments in metallurgy, available materials, and our increasing understanding of orthodontics have brought our field a long way away from the Bandeau. For the purpose of brevity, we’ve only covered the most broad strokes in orthodontics and archwire development, but even the lightest understanding of history of the field and the history of archwires helps to illuminate how fortunate we are in the modern day to have the array of techniques, and depths of study that we do on the effective application of archwires.

The Basics of Archwire Application

An archwire’s shape, material, and style all work together to help create an orthodontic outcome, and each of these factors should be understood and considered before undertaking

Shape & Style – Defining aesthetics and function.

There are two primary Archwire shapes, or ‘styles’, these being rounded and rectangular. These archwires are sometimes used consecutively to one another as the patient’s mouth is changed by effective treatment. It should be noted that the wire itself is what is round or rectangular, with rounded wires being more like a cylinder, and rectangular wires being shaped with 90° corners, and then shaped into the shape of the patient's mouth. See the diagram below for a visual representation.

Rounded Archwires – A long, cylindrical wire, these wires are more elastic thanks to their shape, which means their application of force is more gentle. It’s this gentle application of force which makes rounded archwires perfect for the early stages of orthodontic work.

Rectangular Archwires – This alternative is less malleable and elastic, more rigid. This makes this type of archwire perfect for more impactful and precise movements, typically this comes in the later stages of orthodontic work, such as detailing and finishing.

Full-Size Archwires – These archwires nearly fit their bracket, so as to maximise torque and the force exercised on the teeth they are adjusting. These archwires tend to be much larger by diameter than alternative archwires.

Undersized Archwires - These archwires are much smaller in diameter than full-size archwires and do not fill their bracket, this reduces friction and encourages the use of sliding mechanics.

Archwire Form

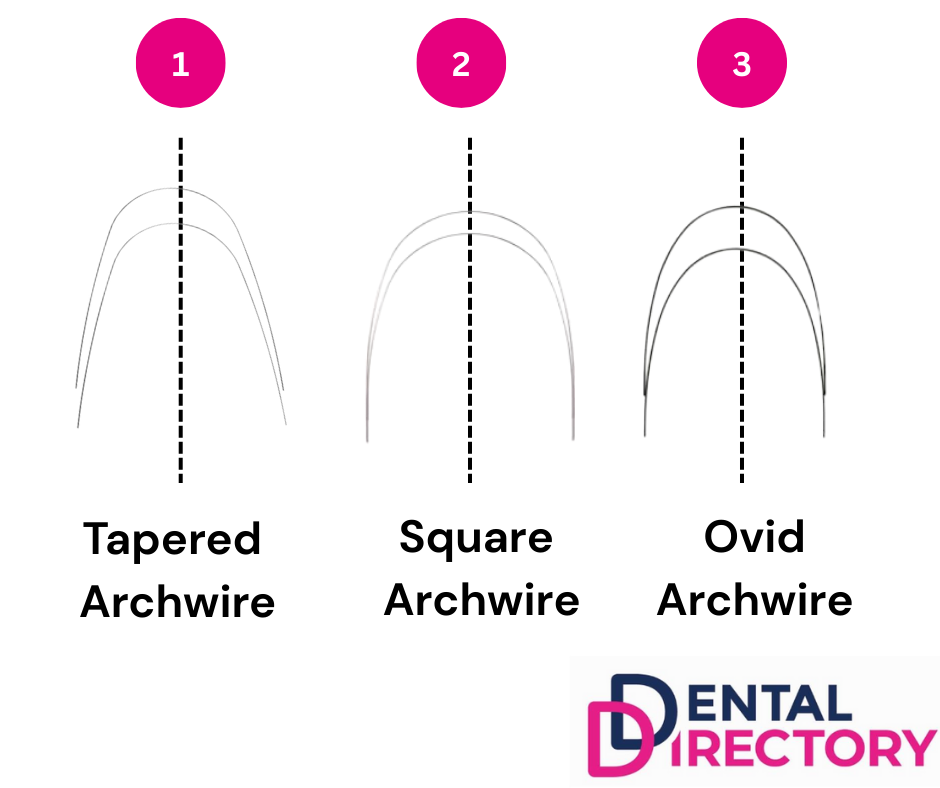

Also known as ‘Arch Forms’, this term describes the shape an archwire is bent into and any variations thereupon. While Archwire shapes describe the shape of the wire itself if you were to take a cross-section, efficacy and applications. There are three main categories for archwire forms that we will be talking about today, however there are multiple variations upon each shape, and many of these variations have their own names.

- Ovoid form – The typical, rounded shape which conforms to the arch shape of the patient’s mouth. Some brands refer to this as a "Full form" arch. There are many different classifications for arch forms, but the Ovoid form is shaped like a rounded oval. The reason this arch form is so widely used, is because it is suitable for most patient archforms, and is particularly good at treating small amounts of crowding, or creating small amounts of spacing. However, its versatility does not allow it to be used in cases where significant arch expansion is required.

- Tapered form – This archwire has a tighter point at its end, while still Ovoid, in a sense, it has a sharper gradiant towards a more pointed end. This is also sometimes referred to as a V-form. Because of the narrow end to this archform, it is best used with patients who have narrower anterior archform, and a wider posterior archform.

- Square form – This archwire has the least amount of curvature, and its anterior region is almost entirely flat. If your patient requires significant repositioning or expansion in their posterior teeth, then this form is the most obvious pick. While this form is effective at prOvoiding a large amount of torque on the effected teeth, it can also cause discomfort in those with naturally tapered arches.

One important factor regarding archwire forms, is that they need to conform to and work with the natural arch form of your patient, so that stability can be ensured throughout the re-shaping process. This means that, naturally, forms such as tapered forms.

It’s also worth saying that the use of preformed arches helps to standardise outcomes and reduce the room for error. So, please use pre-formed arches where possible.

FAQ - How does an Archwire’s dimensions impact its stiffness?

There is a general rule of thumb regarding the relationship between dimensions and stiffness. Generally, the larger the dimensions of your wire, the stiffer it will be, making it easier to control and harder to deform. Smaller dimensions are preferred in some instances because of their higher level of flexibility, but generally, the larger the wire, the stiffer the wire.

Material Matters - Properties, Strengths & Ideal Use-Cases.

The material used in an archwire is undoubtably an important factor in its function and efficacy. We briefly broke down the three primary materials and their use cases in the introduction to this blog post, but there’s a lot more to say, so this section will be spent getting into the nitty-gritty of NiTi, TMA, and SS.

NiTi Archwires -

Nickel Titanium Archwires have two variations, NiTi Archwires and Thermal NiTi Archwires. Both of these types have particularly beneficial properties which give them great utility in orthodontics.

The first benefit is shared bewteen the two variations, this being their superelasticity. Superelasticity (also known as psuedoelasticity) means that a material can be deformed to a much greater extent than ordinary materials and still return to their original form. This makes NiTi a very flexible, useful archwire material.

Thermal NiTi however, improves upon this with a property known as 'shape memory'. This means that a material can be shaped when cold, but will return to its original form when heated, or under certain temperatures.

These two properties mean that there is a greater range of motion in Thermal NiTi archwires for significant readjustments, and when placed in a person’s mouth and heated up to their body temperature, the archwire will exhibit more force on a patient’s teeth. These two properties are excellent for gentle, sustained tooth movement.

However, as mentioned previously, the tensile strength of NiTi Archwires is not as high as Stainless Steel alternatives, meaning Stainless Steel may be a better alternative for the later stages of orthodontic work. Additionally, Beta-Titanium (A.K.A. titanium-molybdenum alloy/TMA) offers an excellent midway point of NiTi’s flexibility and Stainless Steel’s flexibility.

TMA (beta titanium) Archwires -

As previously mentioned, TMA archwires are often considered as an in-between material, bridging the gap between Stainless Steel and Nickel Titanium. These wires have a very good springback, or deformation point, and are very formable, they can be welded or bent without becoming excessively fragile. These wires are perfect for use in finishing, detailing, root control, and segmental mechanics.

Compared to stainless steel, TMA wires produce more torque and encourage movement over longer distances.

SS Archwires -

Stiff, with low springiness low range of movement, Stainless steel archwires are excellent for precise, high-stress applications. Their corrosion resistance is also high enough that they can withstand contact with saliva for an extended period of time.

Additional to Stainless steel archwires, there is a type of archwire called Multi-Strand Stainless Steel Archwires, these are made out of very thin Stainless steel wires coiled together

What are Loop Mechanics?

As the archwire is shaped throughout the mouth, its wire can be manipulated so as to prOvoide specific amounts of force on different parts of the mouth. This is achieved by looping the archwire at specific parts of the mouth to cause tension on a specific tooth. There are different types of loop, and each of them have different purposes. Some examples include:

- Horizontal loops

- Vertical loops

- Combination loops (T Loops)

- Leveling and Aligning

- Retraction

- Multipurpose c. Based on presence of helix

- Loops without helix(e.g. vertical loop)

A loop requires one or more of the following – A vertical force system, a horizontal force system, alpha and beta bends, and a helical component.

Loops close gaps between teeth through three phases. Tipping, where a tooth is rotated at its long axis, or “tipped”. This stage helps to straighten crooked teeth, or teeth which are at an angle. Translation, where a patient’s tooth is moved in one direction or another. Finally, there is root movement, where the root of a tooth is moved to be parallel to the tooth, now in its ideal location.

This set of mechanics is also referred to as “Frictionless Mechanics” due to the fact that its mechanism of closing via loop does not pose a potential risk of friction from an archwire.

What are Sliding Mechanics?

Sliding mechanics are an alternative mechanic to loop mechanics, where teeth are moved along the archwire through brackets, springs, or other means of prOvoiding steady force. The role of the archwire in sliding mechanics is commonly compared to a “track” or “rail”, as the archwire braces against the tooth rotating out of place, and allows force creators such as springs to move the tooth along its length. This allows for precise and efficient movement of teeth in orthodontics.

Sliding mechanics are often preferred in common orthodontic cases, such as closing excess spacing between teeth, closing spaces resulting from premolar extractions, and closing gaps caused by missing teeth. However, in some cases, friction between the archwire, and the closing bracket bonded to the tooth can slow down the rate of tooth movement. Self-ligating brackets and careful planning by an orthodontist can help to reduce this friction.

Archwire Sequencing – Step by Step

Here’s a short example of what archwire sequencing might look like in a standard practice. While it shouldn't be considered a guide, and may not work for every bracket system, the basic steps might look something like the following:

Initial Alignment – Step One

Initial alignment would use NiTi (.012, .014) for gentle alignment and levelling of teeth. This means that the superelastic properties of NiTi, as well as its shape memory, can be used to their fullest effects. This helps to manage crowding, rotations, and deal with irregular arches.

Working Phase Wires - Step Two

The working phase requires stiffer wires, so NiTi or SS is recommended, and this is when space closure, bite correction, or correcting the curve of spee until it is, level and even. The biggest challenge here is managing your anchorage strategies as more torque is being placed on the teeth.

Finishing – Step Three

This may use rectangular stainless steel, or TMA for those final movements, this includes root positioning, as well as detailing bends and customisations.

FAQ - What is Root Resorption?

Broadly, root resorption is when the roots of a tooth are re-absorbed by the mouth, causing instability and potential tooth loss. There are many different types of root resorption, but arguably the most relevant to archwires is Surface Resorption, which can be caused by orthodontic treatment?

FAQ – What Causes Root Resorption in orthodontics?

There are many potential causes of root resorption, but intense or prolonged orthodontic treatment can place too much strain on the teeth and cause root resorption. This means that force must be applied appropriately, carefully, and without putting too much pressure on an individual tooth.

FAQ - What is springback?

This is the measured limit of contortion a wire can have before it is permenantly deformed. This term is also referred to as elastic deflection. A higher springback increases its range of action.

Common Archwire Challenges (and How to Solve Them)

Working with archwires can be difficult, orthodontics is complex and the interactions between your wire and the friction, torque, and force required to get your desired outcome can sometimes feel very obtuse, even to experienced orthodontists. So, we’ve written a quick list of common challenges you might face when working with archwires, and rough outlines of how you might go about solving them. As ever, this list is by no means all-inclusive, and the solutions prOvoided are intended as indications, rather than guidance or advice. We would ask that you please research and seek the opinions of trained professionals before making a decision regarding these issues.

My Archwire Isn’t Fully Engaging Bracket Slots

This is a relatively common issue with wires, and often comes down to size, malleability, and the location of your brackets.

Consider:

- Utilising smaller NiTi wires, for this phase of ortho care.

- Additionally, consider using thermal wires, this means you can deform your wire so that it engages with the bracket, before returning to its original shape.

- Alternatively, reassess your bracket placement.

I Can't Generate Sufficient Torque Expression

Another common issue, torque expression is influenced by a number of factors, such as the dimensions and material used in the bracket and archwire, any twist the wire may have, as well as the bracket’s position.

Consider:

- Moving to full-size rectangular wire. The full-size wire will help you maximise the torque and force you can exercise, and the rectangular wire will help apply that force because of its stiffness.

My Archwire Has Too Much Friction

Friction can hinder and halt many of the necessary steps in orthodontic work, and it should be dealt with as quickly as possible.

Consider:

- Changing archwire material to stainless steel may be a means of reducing friction, as stainless steel tends to be lower friction. In some cases, this might not be possible, as stainless steel’s stiffness may make it not suitable for all purposes. In cases such as this, we’d advice reviewing your ligation technique, as wire size, bracket placement, and many other factors may be contributing to the friction your archwire is generating.

My Archwire is Breaking, or Deforming

It happens to even the best orthodontists, wire breakage or deformation is far from an ideal outcome, and it needs correcting quickly. We’d mostly advise sticking to the fundamentals, and alternative wire materials to benefit from their enhanced malleability.

Consider:

- Always stick to correct bending techniques. These techniques change depending on material, dimensions, and several other factors. An in-depth understanding of the biomechanics at play is absolutely necessary here. Consider utilising digital software to help map out the simulated movement of teeth, and the shape required for your archwires.

- If your forming leads to some bends which require finesse, we’d recommend starting with a material such as TMA, which lends itself to malleability.

My Patient is Experiencing Discomfort

Patient comfort and pain management is always going to be a part of dental work. While in some circumstances, a basic level of discomfort is completely unavoidable, there are a few adjustments you can make which may improve your patient's condition. These improvements include changing your materials and creating small, minimal wire adjustments to help alleviate pressure on particularly sore or painful parts of the mouth.

Consider:

- Using thermal NiTi might be helpful as the material lends itself well to low-force, gentle application of torque. Additionally, NiTi variants may be heat-activated, meaning they have shape memory. This can also help to alleviate discomfort as heat-activated wires tend to fit better and apply their force more gently.

- Additionally, consider making slight and gentle wire adjustments to alleviate pressure on high-tension parts of the mouth.

The Archwire Glossary:

There’s a lot of specialist terms regarding archwires and their uses, here's some of the terms you might hear used, and a breakdown of their meanings.

Load – This is the pressure placed on an archwire by tension and resistance.

Stress - The stress placed on an archwire is reflective of how its load is distributed. Areas with higher tension will have more stress.

Strain - This is when the archwire begins to distort because of its load.

Stiffness – Also known as the modulus of elasticity, stiffness is proportional to the wire’s diameter and inversely proportional to its length or span. The harder it is to deform a wire, the stiffer it is. A good way to understand stiffness is to consider it as the ratio between stress and strain.

Permanent Deformation – When the archwire begins to warp and deform in such a way that it will not return to its original shape nor function as intended.

Yield Strength – The tension point of a wire, once reached, the wire will no longer return to its original shape.

Proportional Limit – This is the initial point at which the archwire begins permanent deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength – This is how much load a wire can sustain.

Failure Point – The point at which the wire will break.

Curve of Spee – This is sometimes also known as von Spee's curve, it is the curve of the mandibular occlusal plane, the curve starts at the canine teeth, and follows all the way back towards the buccal cusps of the posterior teeth.

Proportional limit - This is when the archwire begins to deform under pressure. The first point at which the archwire deforms.

Ultimate tensile strength - This is the maximum load a wire can sustain.

Failure point - The first point at which a wire breaks.

Modulus of elasticity - This is the ratio between the amount of stress applied to a thing (such as an archwire) and the deformation it undergoes.

Load-Deflection Rate – Similarly to the modulus of elasticity, this is regarding the deflection (deformation) that an archwire undergoes under a given load or force.

Range – Range is the amount an orthodontic wire will bend until permanent deformation occurs.

Springback - Springback is the ability of a wire to go through large deflections without being permanently deformed.

Bite – This may be otherwise referred to as an “occlusion,”. This is the way that the upper and lower teeth meet together.

Biocompatability – This is the archwire’s resistance to corrosion and tolerance to the surrounding tissues within a patient’s mouth.

Elastomerics– Some brace types require the use of ligatures, or bands. Sometimes known as elastic ties, these help to hold the archwire in place.

Resilience – This is a term to define the energy required to make a wire deform

Formability – This is the amount of permanent deformation or bending a wire can withstand before breakage occurs.

Shape-memory alloy - This term outlines the ability of an archwire to “remember” and return to its original shape after being plastically deformed.

°